2 Steps for Training with a Back Injury

1. What’s Going On?

As long as there isn’t any radiating pain down your leg, numbness, loss of function or structural damage to the spine, most back injuries a lifter sustains won’t require medical attention. The simple fact is that most back injuries will not be viewable on an MRI, X-ray, or other medical imaging report. Furthermore over 50% of people according to the New England Journal of Medicine reports the general population has a disc bulge, and at least 35% have two or more.

Many are asymptomatic, meaning there's pretty much nothing that can be done to help short of massive invasive surgery that would be completely unnecessary. Most doctors will happily prescribe you a muscle relaxant and tell you to take some time off along with a hefty bill. For the majority of us, taking time off is often not something we want to do.

First thing is to figure out what to do and what to avoid in the gym. The easiest way to go about this is movement mapping. Performing a series of simple movements can help determine which ones cause more pain or less pain, and then use the results to guide you in the gym. It can give you an idea of what may be wrong and what you need to do to fix it, or who you need to see to get it fixed.

2. Get Moving

The majority of acute low back injuries often get better on their own with no intervention within 4-6 weeks. However if it's a chronic problem, the muscles will begin to atrophy and weaken, making future back injuries more likely to happen.

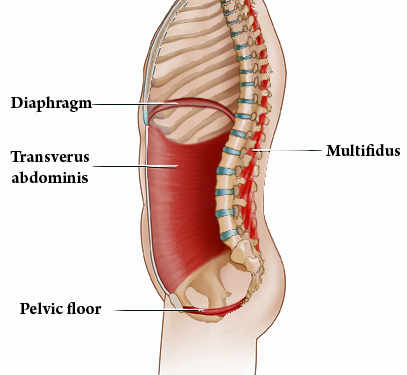

Any movement you perform with a bad back need to be done with the intention of having your core do the bracing for you. The best way to do this is through a concept Dr. Stuart McGill calls "super-stiffness." By contracting all the abdominal, low back, pelvic and intercostal muscles at once, you can increase overall stability of the spine and limit the chance of a buckling injury or any problems with your discs.

To get this idea of super-stiffness to work for you, it has to be 360 degrees of tension. You need to flex your abs as if you’re about to take a punch. Now contract the oblique muscles and low back muscles, and lastly clenching your pelvic floor muscles (anus).

This must be done whenever you're performing any exercise listed below, as well as any type of lifting, pushing, pulling, carries, bending, or twisting.

In other words, everything!

Movement: Flexion

This is by far the most common dysfunction for lower back pain. The majority of disc issues within the lumbar spine involve posterior nuclear migration and cause a bulging of the disc into the central (less common) or lateral (more common) canals, which then pushes on nerves and often leads to intense pain.

The test:

Sit in a chair and touch your toes. If that seems impossible, stop before you hurt yourself. If it’s easy, try to stand upright and touch your toes. Pain or having to slowly climb your way down would indicate a problem and would necessitate that you avoid doing certain things.

Don't Do:

- Deadlifts, bent-over rows, and seated rows

- Spinal rotation movements (twists and chopping movements)

- Sit-ups or any ab isolation movement that forces flexion without co-contraction of the low back muscles.

- Standing calf raises, leg presses and back squats.

- The direct compression on the discs can be extremely uncomfortable.

Do:

- Glute bridges

- Allows you to hit your hamstrings and glutes without placing your spine under any negative loads.

- Front squats or goblet squats.

- Hits the legs without straining the back, and forces the spine to resist being pulled into flexion.

- Any type of chin-up, pull-up, or lat pulldown

- The lats play a huge role in recovery of the spine, as they wrap all the way from the shoulder down to the pelvis, and can add to the stability of the spine.

- Push-up variations.

- These will increase the need for spinal stability over bench presses or dumbbell presses, and can be progressed by elevating the feet and then adding weight via chains.

Movement: Extension

While not as common as flexion-based pain, extension can be just as limiting, but is a bit easier to manage. Most extension-related issues revolve around facet joint issues or even soft tissue compression, so movement that involves extension should be controlled or eliminated.

The test:

Lie on your stomach and prop yourself up on your elbows. If this hurts, or if it simply results in a dull ache, stop doing it and follow the recommendations below.

Don't Do:

- Back extensions.

- Deadlifts.

- Barbell squats.

- The spine has to extend, under compression and against shear forces, to squat. Bad news when you’re unable to tolerate extension

- Overhead pressing.

- The spine needs to extend to move the arm overhead.

- Rotation

- Whether standing, sitting or lying down.

Do:

- Dips.

- The combined effect of core activation and distraction on your spine as you hang your body weight with no force pushing up will feel a lot better.

- Chest Supported Dumbbell Rows.

- This is a great way to continue to train while reducing the shear force within the vertebrae. This helps protect your back while you're hitting your lats.

- Rollouts, also known as straight-arm extensions.

- These force you to maintain some form of flexion throughout, or else you'll feel a small pinching sensation in your low back.

Gives these two tests a try and get back in there. The worst part of having an injury is allowing it to leave you completely debilitated, take back control!